No matter which way you shake it, if you dig motorcycles and working on your own rides, the older vintage models will always hold a solid place of wonder. As far as we advance in technology, older combustion engine mechanisms feel pure and simple and in a way, primal.

The feeling of hearing a bike fire up, after many hours of massaging parts to fit and function is a joy to the ears. Older bikes always require a more hands on approach as they only have the human computer to set the functioning parts in order. The magical charm, resides in the fact that with basic understanding of mechanical principles, most fixes on older bikes can be done with some time earned know how through greasy hands and well earned frustration. At the end of this journey though, the machine and the rider form an inexplicable bond that only they can relate to. Ever wonder why custom rides, always have a nick name?

Do yourself a favor and read into the article below from Collector's Weekly. To learn more about any topic you just have to dive in. The interview below with Darwin Holmstrom may open a few more doors and thoughts about a new project to start over the cold months ahead.

Link to original interview on Collector's Weekly

The feeling of hearing a bike fire up, after many hours of massaging parts to fit and function is a joy to the ears. Older bikes always require a more hands on approach as they only have the human computer to set the functioning parts in order. The magical charm, resides in the fact that with basic understanding of mechanical principles, most fixes on older bikes can be done with some time earned know how through greasy hands and well earned frustration. At the end of this journey though, the machine and the rider form an inexplicable bond that only they can relate to. Ever wonder why custom rides, always have a nick name?

Do yourself a favor and read into the article below from Collector's Weekly. To learn more about any topic you just have to dive in. The interview below with Darwin Holmstrom may open a few more doors and thoughts about a new project to start over the cold months ahead.

Link to original interview on Collector's Weekly

"Darwin Holmstrom talks about the history of motorcycles, especially Harley-Davidsons. He discusses technological and stylistic innovations and specific break-through models, and the differences between vintage motorcycle collectors and classic car collectors. Darwin has written multiple books on motorcycles and automobiles. His newest, “The Harley-Davidson Motor Co. Archive Collection”, is available online from Motorbooks."

|

| Harley Davidson, 1984 Model FXST Softail |

Obviously, if you’re interested in the motorcycle industry and the motorcycle culture of America, Harley-Davidson plays a pretty prominent role, but I’m interested in all sorts of different bikes. I’m actually partial to Victories. They have become very nice motorcycles once they quit being so butt-ugly. They’re not quite as expensive as Harleys, though they’re still not cheap, and they seem extremely well built and very durable. I’ve had nothing but good luck with them. They’re the other American company.

From an intellectual standpoint, I’m impressed with the brilliance of the Harley-Davidson company’s marketing and product positioning. The people at Harley are no dummies. They’ve made a lot of brilliant moves since the buyout from American Machinery and Foundry (AMF), and the most important product that they’ve had since then, the Evolution, was actually commissioned by AMF. Their bikes are beautiful, too. There’s just no denying that they’re the most attractive motorcycles available anywhere.

One of my favorite bikes is the counterbalanced Softails. If I could get that engine in a touring bike with a stiffer frame, I’d have a Harley. As it is right now, you can get a bike like that, but Victory makes it, not Harley. That counterbalanced engine in the Softail is critical to me because I’m a long-distance rider. The non-counterbalanced bikes Harley makes are fine if you don’t put a lot of miles on them. I used to do a lot of marathon-type riding, time-distance rallies, that type of stuff, and if your engine’s not balanced, the bike’s going to shake.

Right now I’m in the process of a year-long recovery from an accident. It was a minor crash last year that should’ve been nothing, but I landed on my knee and pretty much destroyed it. I’m still recuperating from a bad racing crash I had six years ago as well, so right now all I’ve got is an Italian bike that shall remain nameless, but I haven’t licensed it yet. I’m not even sure it’ll start.

Collectors Weekly: What about some of the other bikes you’ve owned?

Holmstrom: I’m critical. I’ve got complaints about all of them. Writing for magazines and stuff like that, you’re always looking for the flaws. It’s like asking a movie critic about their favorite film.I had a Triumph Sprint, a sport-trim bike that I liked a lot, but it never quite got the fuel injection right. I’ve had some Yamaha sport bikes that I’ve liked, but there were a lot of transmission issues with Yamaha motorcycles. As far as I know, they still have the same issues now.

The last bike that I was just absolutely crazy about was probably a Yamaha I bought as a carryover in 1985. I guess the two bikes that I’ve had that I unequivocally liked the most were a Victory Vegas and a Victory Hammer. I’ve got no real complaints about either one of those.

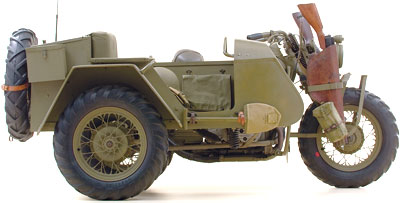

I also really love the Urals with the sidecars, the Russian bikes. It’s just as hard to ride a Ural sidecar at 55 miles an hour down the highway as it is to ride a high-performance sport bike on a racetrack at 150 miles an hour. There’s a sticker on the gas tank that says, “Warning: Right and left-hand turns can be dangerous,” and it’s got little skull and crossbones on it, which is true. Right-hand and left-hand turns can be extremely dangerous on a sidecar because it’s a totally unstable vehicle, but going straight can be pretty exciting. They’re so counterintuitive, you have to do everything the opposite of what you do in a motorcycle. It’s the same kind of focus you need to ride fast on a racetrack. They’re like time machines. It’s like getting on a brand new motorcycle from 1939.

Sidecars are pretty collectible now, especially BMWs. A really nice classic BMW sidecar costs as much as a new Japanese motorcycle, but that’s a pretty limited market. I wouldn’t buy one for an investment. I wouldn’t buy any vehicle for an investment right now. You just buy it because you like it and it’s fun.

Collectors Weekly: Do collectors ride their bikes?

Holmstrom: A lot of them do. Most of the collectors I know ride up to events and stuff like that. There’s not a whole lot of difference between a BMW from the 1930s and a BMW from the 1960s. They’re pretty simple machines to keep running and they’re pretty well built. Same with Harleys—almost all of the Harleys ever built are still on the road. Very few people junk out their Harleys and throw them away, maybe with the exception of some of the Sportsters from the ’70s.Collectors Weekly: How did motorcycles evolve?

Holmstrom: The very first internal combustion engine vehicle was two-wheeled and wooden. Gottlieb Daimler was working on a four-stroke engine, and to test it he cobbled together this two-wheeled wooden vehicle. So the history of the motorcycle actually goes back further than the history of cars.In the early years, motorcycles were fighting with cars as basic transportation. When Henry Ford applied mass-production techniques to the automobile, he brought the price down to the point where the motorcycle could no longer compete because cars are always going to be more practical than motorcycles. So motorcycles went through a period of hard times and evolved as a sport vehicle. Ever since then, the history of motorcycles has been peaks and valleys, booms and busts, right up until today.

Actually, motorcycle sales are holding pretty steady right now. They’re doing much better than car sales. The little scooter markets boomed last year with the rise in gas prices.

|

| Model XS with sidecar |

Honda started importing bikes in 1959, and they really came heavily onto the scene in the early ’60s with the Dreams and Scramblers. Their first big bike was in 1969, the CB 750. At that time, there was also this massive influx of 10 million people hitting the market, the baby boomers. They were entering the age range where they could afford to buy bikes, so they fueled this boom right up into the late ’70s, early ’80s. The number of motorcycle registrations was just phenomenal.

Then they had a big bust in the early ’80s because the baby boomers were all getting older, their kids were growing up, and they were getting too busy to ride motorcycles. By then, motorcycles had gotten so expensive that there weren’t a lot of inexpensive options for young riders to get into the sport. We had a crash that almost took Yamaha out of business, and that’s when Harley was bought out by the group of investors from AMF.

Collectors Weekly: What were some of Harley Davidson’s innovations??

Holmstrom: First of all, they developed a new engine. The Harleys that they sold up until 1984, the Shovelheads and the Sportsters—you know when I said how bad motorcycles used to be? They were still that bad. AMF ramped up production so that Harley was just cranking out motorcycles and the quality suffered. Not only were they running around with 1930s-era engineering, but the quality control was in the toilet. Then they developed the Evolution engine.“The Knucklehead was a pretty big deal because it had overhead valves.”It put them on par with where the Japanese were in maybe 1969, but that was good enough because the Japanese bikes of 1969 were really good motorcycles. You can find them today sitting in people’s garages, and you can just put a little oil in them, maybe some new plug wires and a new battery, and then start them up, even if they’ve been in that garage since 1983. They’re very well-built bikes, so that’s not the dig it sounds like, but the Japanese had moved on by 1984 when the Evolution came out. For the first time you could buy a new Harley Sportster and ride it for years and years without any trouble and without needing any special mechanical skills whatsoever.

So first they made Harley-Davidsons accessible. Then they decided to really mine their heritage. In 1984, they made the coolest custom bike anybody had ever seen. It was like the Chopper, only you didn’t have to build it yourself in a garage. Then they came out with the Heritage Softail which looked just like a 1951 Hydra-Glide, which was a very coveted bike. But the Heritage was modern, with all new parts. It ran well and you didn’t have to overhaul it all the time.

What Harley still doesn’t do well is reach young buyers. Harley owners are aging and the company’s attempts to market to younger buyers are painful to watch, frankly. They show people on these custom Harley cruisers with snowboards strapped to their back. If you’re going after the 20-something adrenaline junkie crowd, you’re not going to get them with the bikes that Harley offers, no matter how many cool snowboarding video clips you put on your website. On a good day, a Harley-Davidson is going to crank out maybe 72 horsepower at the rear wheel. A new Yamaha R1 or a GSX-R 1000 Suzuki or a Honda CDR 1000 RR are going to crank out 172 horsepower at the rear wheel.

Collectors Weekly: Do people tend to specialize in their collections?

Holmstrom: I don’t know anybody who only collects Harleys. I know people who just collect BMWs, but they’re a different group of people. They tend to be pretty rigid. But people who collect motorcycles generally collect motorcycles. They might gravitate towards American bikes or towards Italian bikes or German bikes.Oddly enough, Harleys aren’t the most valuable old collectible bikes. They usually cost more than a Triumph or a BSA, but they’ve always been relatively affordable compared to, say, a Vincent or something like that. I think people are as likely to buy a vintage motorcycle to ride as to collect. They don’t sit and collect dust in museums in collections as much as they are out on the road.

Collectors Weekly: What’s the deal with restoring motorcycles versus leaving them in their original condition?

Holmstrom: You don’t see a lot of what you call time-capsule bikes simply because of the way most of those bikes were built. They pretty much needed to be overhauled every winter.Everybody modifies their bike, so when the Harley Archives buys a bike that’s from outside, a lot of the work they do is to get rid of the non-stock pieces and bring it back to stock condition. One of the hardest things to do is find stock bikes for Harley calendars because most Harleys have aftermarket seats, windshields, luggage carriers, wheels, chrome, carburetors, pipes, et cetera.

Collectors Weekly: In terms of appearance, do collectors care about things like whitewall tires and chrome or are they more concerned with function?

Holmstrom: If you’re going to restore a bike, you want to make it as correct as possible, so whatever it came with is what you put on it. But like I said, people don’t usually restore them, they modify them. I know more people that are into making period-correct customs than historically accurate restorations. They only use the aftermarket accessories that were available at the time. That’s where some of the really cool bikes come from.There’s a bike in The Harley-Davidson Collection called the 1942 Model WLA “Russian” Boozefighters Cutdown Replica. That’s an example of a period-correct custom. It has all the different parts that would’ve been available at the time. I know plenty of people who are doing stuff like that.

Collectors Weekly: What is Harley’s long-term impact on the motorcycle industry?

|

| Harley Davidson, 1903 Serial Number One |

Holmstrom: They kept the American motorcycle industry going for 50 years. Before World War II, Harley-Davidson was among the world’s greatest technical innovators when it came to motorcycles. Afterward, they became much more conservative, but they were the last surviving American motorcycle company for 50 years.

Stylistically, Harley invented the Cruiser, the factory concept, and they pretty much invented the heavyweight factory touring bike with their Electra Glide. For a couple of decades, their stylistic innovations were few and far between, but then they came out with things like the Heritage Softail in the ’80s and revitalized the whole motorcycle industry. That was true right up until the early years of this decade.

Collectors Weekly: Could you tell us a bit more about the Knucklehead?

Holmstrom: In the early years of motorcycling and transportation, there were no generally agreed-upon design principles. Everybody made it all up from scratch. The earliest engines were these intake-over-exhaust-types that were so crude, we wouldn’t even recognize them as a gasoline engine today, but that was the leading edge in technology. They were working in a completely different world. We didn’t have the kind of aluminum alloys that we have today. We didn’t understand metallurgy like we do today. You couldn’t make something as precise as you can today.Plus there were a lot of challenges from the gasoline that was available in the early years. I doubt you could run your lawn mower on it today. There were all kinds of limitations as to what they could do. This whole development of the engine is this interplay between improved production techniques, improved metallurgy, and improved fuels. Each one allowed improvements in other areas, but nobody had a template to go from.

The Knucklehead was a pretty big deal because it had overhead valves. First, they were atmospheric, and then they were mechanical, so they had pushrods and lifters.

The Flathead engine, the side-valve engine, made sense for a while because it was a good, efficient way to get horsepower out of lousy, low-octane fuel. Indian was an early champion of the side-valve engine. Harley’s side valve, their Flatheads, were almost like a distraction for the company during the Depression. Indian was focusing on developing side valves, so Harley went ahead and developed an overhead valve engine, which was cutting-edge technology at the time, and that was the Knucklehead. That was pretty revolutionary. The really hot European bikes were using overhead valve engines, so it was sort of like if Harley made a bike today that was competitive with the fastest Ducati. They were a pretty big deal.

Harley got behind in the postwar years. Because of the rebuilding in Europe, European manufacturers were allocated resources before Harley was, so the company got behind at that point, and then 10 years later, the Japanese came along.

Harley didn’t really catch up until 1984, and they did so by making their own curve. They wisely decided not to compete with the Japanese head-to-head in their own game. They went their own way, which proved to be a way that people wanted to go. There are a lot of people out there who really don’t care about having 172 horsepower in their rear wheel or being able to do a wheelie at 90 miles an hour. Unfortunately, the younger buyers that they’re trying to woo now do.

Collectors Weekly: In your book, you said that Harley raced in the 1900s. Could you tell us a bit more about that?

|

| 1975 Model XR-750 Dirt Track Racer |

Holmstrom: Harley chose a technological path early on and they stuck with it. It actually lent itself really well to American-style dirt track racing, but they had a road racing effort throughout the 1990s and into the early 2000s that was less than successful.

For many years, Harleys were competitive in drag racing—they have the All Harley Drag Racing Association. In 1994, they released the Dragster, and then in 2006, there was the Harley-Davidson V-Rod Destroyer. That was a V-Rod factory drag bike. Anybody with the money could walk in and buy this thing and go drag racing. It does really well in all forms of drag racing.

The area where Harley has been just absolutely dominant throughout history is dirt track racing. The Model XR-750 Dirt Track Racer is still the bike to beat. The low-revving pushrod V-Twin just flat out works for this type of racing. It’s ideal for American-style racing. The Japanese have tried like hell to compete with them. Suzuki made a strong effort, but Harley owns that.

They raced all over. The great thing about dirt track racing is that a lot of the dirt track racetracks are just old horseracing tracks. That’s how it got started in the U.S. They started using these horseracing tracks in fairgrounds all across the country, and that became the American style of racing. It’s very cool to go see. It’s dangerous and I’ve seen way too many people I know get killed, but it’s probably some of the most exciting racing you’ll ever see.

Collectors Weekly: Could you tell us a bit about Harley-Davidson’s involvement with World War I and World War II?

Holmstrom: They made a good decision in World War I. Their involvement was relatively minimal. Indian was the big company up until World War I, and Harley was a distant second. When the war started, Indian decided to basically abandon the civilian market to focus on the military market. Harley sold bikes to the military as much as they could, but they didn’t abandon their civilian bikes. They still developed and built bikes for the public and they surged ahead in civilian sales at that time. From then on, it was all downhill for Indian.During World War II, they didn’t have a choice. The government had shut everything down to focus on war development. They sold a lot of bikes to the military, but then Jeeps came along and pretty much ended the need for military motorcycles. Anybody could drive a Jeep, but you had to know how to ride a motorcycle.

The 1942 Model WLA was the main bike that Harley built for the war, and then there was the Model XA, which was a bike they developed to military specifications—it looks like a BMW. They made over a thousand of them before the army canceled the contract.

Then there was the Model XS with a sidecar, which was a prototype they developed. They only built three of them because the military came out with the Jeep about the time they were developing it and they didn’t need it anymore.

Collectors Weekly: What are some other prototypes that were never released?

Holmstrom: There was the 1975 Model OHC-1100 Experimental, which is one of my personal favorite bikes. The thing that strikes me about this bike is that a couple of years later, Yamaha came out with a bike, the Virago, that’s got so many of the same design features as this, it almost looks like somebody from Harley smuggled the engineering drawings out over to Yamaha. The technology is so similar, it’s almost hard to believe it’s a coincidence. Harley is obviously not accusing Yamaha of stealing their design, but I personally think Harley would’ve had a comeback 10 years earlier than they did if they had made that bike. |

Harley Davidson, 1949 Hydra Glide

|

They have a lot of prototypes that were never produced, but most aren’t as striking as these. They’re just variations of whatever they were already making. In a way, they made the right choice, because they decided to focus on a more traditional bike, like the 1984 Model FXST Softail. This was where their market was at. They would’ve been competing head-to-head with the Japanese if they had made that Nova. They would’ve been having comparison tests between this and the Gold Wing, and the Gold Wing would probably beat it incrementally just because it’s Honda.

There had never been anything like the Softail before. There had never been a bike with this kind of styling. It had all the attributes of a Harley-Davidson that people lusted after in a modern, user-friendly package. If you look at the 1983 Model FXDG Disc Glide and then look at the Softail, it doesn’t seem to be that huge of a difference. But if you look at the engine, the Disc Glide has more in common with a 1936 Knucklehead than it does with that 1984 Softail. They went from 1936 technology to 1970 technology. That modern technology put the Heritage Softail in a motorcycle that looked like it could have been made in 1950.

Collectors Weekly: What are some of the most collectible Harleys?

Holmstrom: If you want to talk about the ultimate collectible vehicle, look at the 1903 Serial Number One. That’s the first Harley motorcycle and they only made three of them. How do you put a value on that? I don’t think you can describe it with any word but priceless. I bet if you went up to the Harley-Davidson archives with $15 million in cash, they’d just laugh at you. This may well be one of the most valuable vehicles ever made.Usually the stuff you see changing hands is stuff more like a 1949 Hydra-Glide. The 1934 and 1935 Model VLD used to be relatively cheap. I lost track of the collectors’ motorcycle market the last six or seven years, but back then you could pick up a really nice bike like that for about $10,000, which is not bad. I’ve seen one low-mile original Knucklehead go for $36,000. It was all original with 300 or 400 miles on it; one of these time-capsule vehicles. That was the highest I’ve ever seen a Harley go for, but just your run-of-the-mill Vincent would have gone for that much.

There’s just a different attitude about Harleys. I think people look at Harleys as bikes to ride, whereas a Vincent is a bike to behold in a state of aesthetic arrest. Most end up as custom bikes, which is why you don’t see so many old Harleys being bought and sold by the original-air-in-the-tire crowd.

Customizing is a pretty personal thing. None of the constructs that apply to the collector market really apply to the culture that surrounds custom bikes. You’re more likely to find a bike like the 1973 Model FLH-1200 Electra Glide Rhinestone Harley-Davidson, customized by Margaret and Russ Townsend and covered in red, white, and blue rhinestones and lights, than you are to find a bike that looks like the standard 1968 Model FLHFB Electra Glide. So when you talk about the collector market and try to apply values as if you were talking about a sports car, even a British Triumph or Norton, it’s all apples and oranges. This market and this culture are so different.

Collectors Weekly: What type of people tend to collect and customize vintage motorcycles?

Holmstrom: They’re curmudgeonly and stubborn. I’d say your average motorcycle collector is unmarried and has at least one ex-wife. You should go to an antique motorcycle club gathering sometime. You’ll see the most eclectic, bizarre, fetishishtic collection of machinery that could ever be gathered in one place. And there’s no categorizing the people. You’ll see everything from hippies to tweed-cap Brit expatriates who used to fly spitfires during the Great War. They defy pigeonholing. The car collecting community is much more homogenous.There are shows all over the country, and sometimes they’ll have a theme. One year’s theme might be prewar British bikes, and they might have a special section set aside for people to display their prewar British bikes, but it’ll still be the same eclectic hodgepodge of miscellaneous cool bikes that it always is. Sometimes they have a theme because it’ll help people decide which bike to bring. It’s like, “Should I bring my Ducati round case Devil Drive or my pristine sand-cast 1969 750 Honda?” People tend to have multiple bikes because it’s a lot easier to stick a whole bunch of bikes in your garage than it is cars without the neighbors knowing what kind of a psychotic freak you really are.

Collectors Weekly: What should new collectors look for?

Holmstrom: Look for whatever makes you happy. Even if you get a vehicle that depreciates—and this is true of cars or motorcycles or guitars or whatever—look for whatever makes you happy. In the end, it’s what thrills you that counts. It might be a 1971 Pontiac GTO instead of the cool 1968 or ’69 that everybody else wants. If you’re going into this as an investment, you’re going to end up like the banks that bought adjustable-rate mortgages—you might get lucky, but most likely you’re going to get hosed. Buy something because you love it. It doesn’t matter what anybody else thinks about it, whether they think it’s corny or stupid. You love it and that’s why you have it. It makes you happy, and ideally it’s something you have fun using.Collectors Weekly: Are vintage Harley-Davidsons popular worldwide?

|

1975 Model OHC-1100 Experimental

|

I’ve put well over 50,000 miles on Harley engines. I’ve been stuck in a lot of deserts and cities, hot freeway traffic and stop-and-go traffic, and every single time that it happens, the engine seems like it’s had a little life taken out of it. There’s a reason that cars aren’t air-cooled anymore. That’s why they came out with the V-Rod. It’s going to become increasingly hard to meet emission standards with air-cooled engines.

Honestly, the one thing Harleys do better than anything else—and this is very important—is look good. No other bike is as good-looking as a Harley. Functionally, they’re as good as any other bike using similar technology.

Collectors Weekly: What are some good resources for people who are just starting to get interested in vintage motorcycles?

Holmstrom: My book, The Harley-Davidson Motor Co. Archive Collection, is terrific, because if you’re serious about restoring Harleys, you’re never going to find this much information or photography in one place. I also edited a book on BMW bikes called The Art of BMW Motorcycles. It’s got studio photography of really beautiful BMWs from the very early years up to the most recent ones. BMW motorcycles is a big collecting area, too, but maybe I’m biased because I live in a BMW market. Around here, near Minneapolis, I know more people who collect BMWs than Harleys.The Antique Motorcycle Club of America has a really good website with everything you need to know about upcoming shows, and then there’s the American Historic Motorcycle Racing Association, AHRMA.org."

(All images in this article courtesy Darwin Holmstrom and his book “The Harley-Davidson Motor Co. Archive Collection” available online from Motorbooks.)