In 2013 we will have quite a few new albums coming out on vinyl records. There will be 7" records, 12" records and damn if there won't be some amazing tracks as part of those releases. One important person in the vinyl record resurgence is the one and only Jack White. Third Man Records is now one of the biggest vinyl sellers in the world and below is a really cool write up from Ben Blackwell who heads up the vinyl production within Third Man Records.

|

| Jack White, musican, business man and vinyl record champion for the music fans |

You hear so many stories about that damning phrase, “in perpetuity,” on contracts. Jack was savvy: he didn’t just jump at the first offer he got. He dictated his own terms and got exactly what he wanted.

Come 2008, the White Stripes’ original deal with V2 Records in North America had expired. They signed for “Icky Thump” with Warner Bros., and Warner Bros. also took on the manufacturing of the White Stripes’ CD back catalog. But the band retained the vinyl rights.

The main impetus for starting Third Man Records in 2009 was getting these White Stripes records—their back catalog—back into print on vinyl. In between the germination of that idea and the actual opening of Third Man, The Dead Weather formed and recorded an album, which redirected us for the first year or so. But now we’re back on point, working on these White Stripes reissues.

Collectors Weekly: What kind of facilities does Third Man Records have?

Blackwell: The store itself is fairly small, maybe about 15 feet by 15 feet, maybe a little bigger. We’ve got a little hallway that leads back to our offices. The offices aren’t open to the public, but the hallway is lined with a display of gold and platinum record awards. Mainly two to three people oversee the store, with a fair amount of help from everyone else.Almost all of our releases have been recorded at Jack’s recording studio, which is at a different location than the store and offices. We’ve also done a couple reissues, which obviously weren’t recorded there.

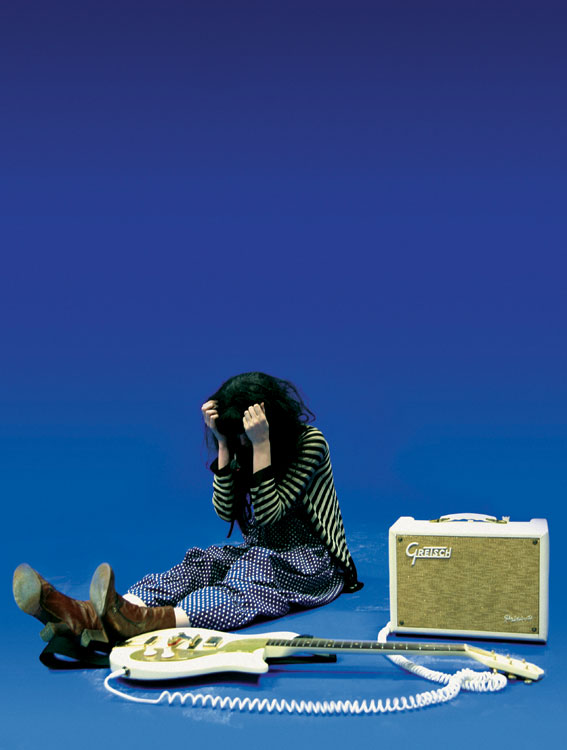

In terms of what we have here at our offices, I think our biggest asset is our performance room, which is called the Blue Room. The covers of the 45s we’ve done from our so-called “Blue Series” were all shot in that room—each has a vivid blue background behind the artist’s portrait.

That’s really the foundation of the building. It’s in the back and holds approximately 300 people. It’s where The Dead Weather played their first show and where they played the live streaming version of “Sea of Cowards” a couple months back.

Dex Romweber Duo has played a show there, as did Conan O’Brien when his band was coming through in June. We also had Karen Elson play, plus a punk band from California called Nobunny.

We also have a fully operational darkroom. We don’t have on-site record pressing, but it’s something we hope to accomplish further down the line.

Collectors Weekly: Where are the records pressed?

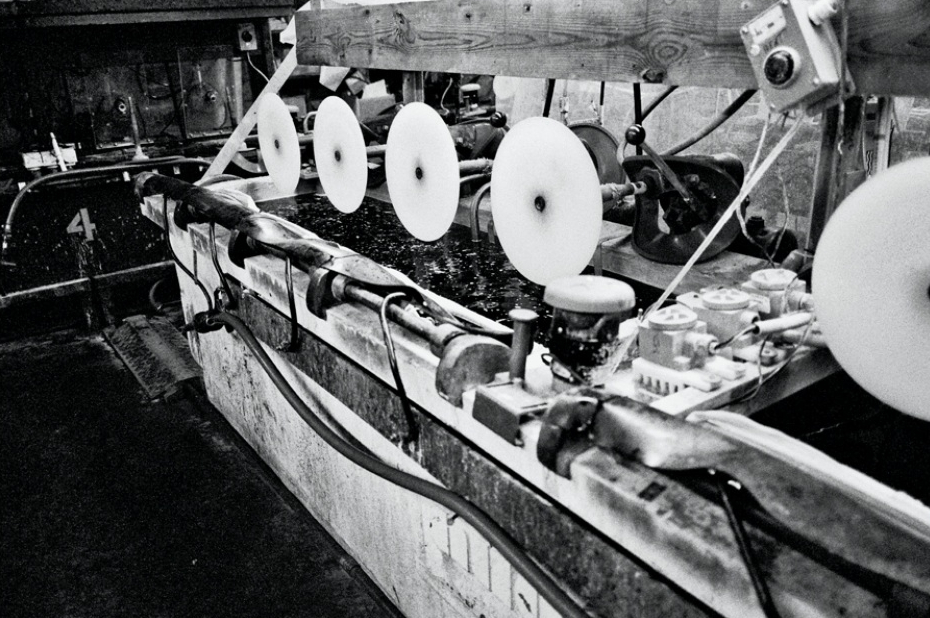

Blackwell: United Record Pressing is approximately a mile and a half from our offices, so they’re literally down the street. They’ve been pressing records since 1949, first as Southern Plastics and then under the United name starting in 1971. It’s a really amazing place.Jack White is the unifying aspect of all our releases. This label is fueled by his energy.From what I can tell, United seems to be the largest pressing plant in the world, both by capacity and square footage. They can crank out a lot in a day. They’ve got 7-inch, 10-inch, and 12-inch presses. They do 180-gram records, as well as all different kinds of colored vinyl.

For our Texas pop-up store, we had this idea of doing oversized records because everything’s bigger in Texas. So United pressed 8- and 13-inch records for us. I don’t know if anyone had actually done 13-inch records before.

It’s a not-so-secret secret weapon, being in the same town as your pressing plant. I can go over there and see my records being pressed, and I can deal with my customer service rep face-to-face to get answers in real time. You don’t really get that connection with someone when you’re just emailing or placing a phone call, which all ties back to our analog approach in some respects—it’s a more old-fashioned way of doing things.

United works with all kinds of major labels, including Motown back in the day. They do a lot of record pressing for Sundazed Records, the Universal family, and small labels like HoZac. Until the mid-’90s or so, they only pressed 7-inch records. Going in there kind of feels a little bit like stepping back in time.

Collectors Weekly: How are vinyl records made?

Blackwell: First off, vinyl as it is right now has a lead component to it, which is obviously not terribly safe for consumption. You don’t want to eat it. There are moves toward working with a lead-free vinyl, which would be better for everyone. |

| Mildred of Mildred and the Mice met Jack White in a Kentucky hardware store. She sang a song for him and he signed her on the spot, making her the first non-Jack White artist for Third Man. |

That raw vinyl is fed into a machine called a hopper, which melts the pellets down and moves them into the extruder. The extruder pushes the vinyl out in strings, which are then formed into what we call a puck or a cake because it looks like a hockey puck or a small, flat cupcake. That cake is very hot, so it’s malleable. Labels are affixed to the cake’s corresponding A and B sides.

A lot of people don’t realize that the labels lend structural integrity to the record itself. Those labels are baked on there. They’re in the press. A lot of people think they’re affixed afterwards or that they’re stickers. That’s not the case.

After the labels are in place, the record is slid into a machine that exerts between 10,000 and 20,000 pounds of steam pressure, depending on whether you’re pressing a 45 or an LP. The puck is pressed against a plate with ridges that correspond to the actual playable audio, which makes grooves on the puck.

The record then slides out of the press and moves toward a turntable that trims off the excess, what I guess you could call the crust of the vinyl. The trimmed crust falls into a bin underneath. The record slides off into a spindle and is then inserted by hand into a paper sleeve.

The Cadillac of record pressing is 180-gram vinyl.The excess vinyl, the crust or the trim, plus any defective records that are scratched or off-center, are all ground down and used in subsequent pressings. For a petroleum product, an oil-based product, there’s actually very little waste involved—there’s a lot of recycling that goes on with vinyl record pressing.

For a regular pressing, I think the percentage is 90 percent virgin vinyl and 10 percent regrind. United also runs specials—what we call the hippie special or the green record pressing—in which they can press on 100 percent reground vinyl so that you’re reducing your carbon footprint. Top-of-the-line 180-gram records, on the other hand, are pressed with 100 percent virgin vinyl.

Collectors Weekly: What is significant about 180-gram vinyl?

Blackwell: The main indicator of a vinyl record’s quality is its weight. The standard weight of an LP is between 140 and 150 grams. Most records you grab are going to be that. The Cadillac of record pressing is 180-gram vinyl, which is heavier and a little bit thicker. There’s a lot of misinformation about it, though. Some people think 180-gram records have deeper grooves, which is supposed to improve the sound. Not true. Records have a standard groove depth, and your turntable wouldn’t really be able to play anything deeper. |

| Part of the mission of Third Man Records is to keep LPs such as "Broken Boy Soldiers," the debut album of the Raconteurs, in print on vinyl. |

The second thing is that 180-gram records are less susceptible to feedback between your turntable and your receiver, depending, of course, on what kind of stereo record player setup you have. I believe it cuts down on drag or interference between the actual turntable and the stylus, your needle.

There’s not really an equivalent for 45s, definitely not at United. There’s also GZ Vinyl, which is in the Czech Republic and is probably the second biggest plant in the world. They do a 45 that kind of feels like if you threw it at someone’s neck, it would cut their head off. I don’t know the exact weight of that, but it might be something like 100 grams.

Lots of artists ask me for advice on pressing records. There are approximately a dozen record pressing plants in the U.S. today. I always recommend the record-pressing plant in their town. You’re going to get a little bit better service than if you’re calling someone or emailing someone. You can go there and walk right in. That’s just a fact.

There are plants in places like Detroit, Cleveland, Nashville, and Columbus. Southern California has a bunch. There’s a handful on the East Coast, and I believe there’s still one in Texas. They’re around. So if there’s a plant nearby, use it. Support your local businesses. It’s going to help you in the end.

Collectors Weekly: What is electroplating?

Blackwell: Here’s the short version of how a record comes to be. Let’s say I’ve got a finished recording. I take that to a vinyl-mastering engineer. United doesn’t do that in-house, but the company that does it for them is literally across the parking lot, an independent company called National Record Productions.The engineer has a really important tool called a lathe. Starting with a blank, empty acetate—or lacquer, as they’re sometimes called—he uses the lathe to cut the physical grooves that will be pretty much the same grooves that are on your playable record.

Once the vinyl-mastering engineer has cut the grooves, the finished lacquer, or acetate, is sent over to United to be electroplated, which involves coating the lacquer with a thin layer of silver that’s then delicately peeled off. Next in the process is nickel-bath electroplating, which makes the stampers from the peeled and electroplated silver. The stamper is what you actually affix to your record press to be stamped into the molten vinyl with the 20,000 pounds of steam pressure I was talking about earlier. In other words, electroplating creates the plates you use in the press.

United also has a really big finishing department, where they insert records into jackets, do shrink-wrapping, run the stickering machine, and so on, in addition to a distribution department and lots of warehouse storage. It’s a big operation.

Collectors Weekly: How is multicolored vinyl made?

Blackwell: We’ve done a few color combinations, including the split-color black and blue LPs. Basically, you have two extruders, each one filled with a different-colored vinyl. Those two extruders feed the molten vinyl into something that looks like a cupcake mold, more or less. |

| "Horehound," the debut album by Jack White's latest band, The Dead Weather, featured two LPs, one in traditional black and a second in white and yellow. |

It’s a little bit different for the tricolor 45s that we do in black, yellow, and white because that is not an automated process. All of our tricolor 45s are done by hand—they’re cut by hand, reassembled with the different-colored portions, and then inserted into a manual press. During the whole process, there’s something like a hot plate around it to keep it at a high enough temperature so it doesn’t solidify. Someone has to press a button for every record pressed. It’s way more labor-intensive, but I think the tricolor vinyl has become our calling card.

Collectors Weekly: Has Third Man done any other special, unique vinyl pressings?

Blackwell: We released a song called “A Glorious Dawn.” We credited it to Carl Sagan, but it’s basically audio taken from his “Cosmos” television series, remixed, rejiggered, and accompanied by a backbeat. We were introduced to it via a YouTube clip, and as soon as Jack saw it, he said, “We have to put this out.” So we contacted the guy who put it together who was really accommodating, and then we called the estate of Carl Sagan. They were very interested and could not have been more helpful.We did a limited release for that record and called it Cosmos-colored vinyl. It was basically black vinyl with little glow-in-the-dark specks—if you held it up to the ceiling, it didn’t take much imagination for the record to look like the universe or the night sky. I don’t think I’ve ever seen that before. To make that, United used raw, glow-in-the-dark vinyl—they just threw a handful in for each record.

When we did a pop-up store in London one Halloween, we took all the 7-inchers that we had pressed up to that point, repressed them on glow-in-the-dark vinyl, and coupled each release with new Halloween-themed picture sleeve artwork. We did 100 each of those titles—the demand far exceeded the supply. People are paying a couple hundred bucks each for them now if you look on eBay.

Collectors Weekly: Where is Third Man’s album art printed?

Blackwell: For our 7-inchers, we use a local printing company called TFS Graphics. They’ve been absolutely wonderful for us. For our LP jackets, we use a company in California called Stoughton Printing. They are the go-to place to get record jackets done right. That’s not the kind of thing that you can do locally. There are only a handful of printing presses that can do all the folding and gluing properly. |

| Karen Elson's "The Ghost Who Walks" LP was produced in an edition of 300. The vinyl was peach colored and scented. |

We’ve used that on The Dead Weather’s “Horehound.” Most of our jackets are done with that old-style tip-on sleeve. It’s printed on a solid, sturdy stock that really looks and feels good. Actually, that’s what we’re all about—looking good and feeling good.

I think people can tell the difference when they hold our records—they look at it and they say, “This wasn’t just dashed off in 20 minutes. They worked hard at this.” At least, I hope that’s what people are taking away from it because we do work extremely hard on every release.

Collectors Weekly: Is Third Man geared specifically toward collectors?

Blackwell: I think we do get accurately pegged as catering to a collector market and to people who are record collectors, but at the same time, the idea behind Third Man Records is that all of this stuff will be in print for eternity. If you want to buy a copy of the first Dead Weather 7-inch—and if you’re not a super-collector who has to have it on tricolor vinyl—you will be able to buy that from us for something like $5 from here until this place falls apart or the world ends. |

| Jack White plays drums for The Dead Weather, seen here in their first public performance at Third Man Records. |

I’m a music fan first and a record collector second. I think that’s something that we try to keep in mind here. People sometimes complain, saying, “I couldn’t get your 8-inch records in Texas or your 13-inch records,” or “I couldn’t get the glow-in-the-dark records in London.” Those records were made to celebrate an event. The point is that you had to actually be there.

Just because no one’s going to sell one million copies of an LP ever again doesn’t mean that vinyl is dead.We also get a little bit of a flack for not making this stuff available online to the worldwide market. To those critics, we just have to respond by saying that they are totally missing the point. One of the ideas behind Third Man is that not everything is just available with the click of a mouse. A lot of what we try to do is meant to be a part of a tangible, real experience.

When we started out pressing the tricolor vinyl, we were pressing 100 copies of tricolor 7-inchers, and they were only available at our storefront. People were pissed—some of them are still pissed about it. Seeing how well it went over, but trying to respond to the complaints, we’ve tweaked it a bit. We still make 100 available in our storefront. People line up and wait overnight outside of our store to get them; some will get proxies in there, and people will flip them on eBay, all that stuff. But we also press 50 copies that we insert randomly into mail orders for that title. So you never know.

Collectors Weekly: Does Third Man sell anything besides vinyl?

Blackwell: Yes. The idea was that if you’re a Jack White fan, if you’re just a fan of the stuff that he’s done, it’s kind of a one-stop shop. If you need a Raconteurs T-shirt or a White Stripes CD, you can get it at our store. We understand that our proclivity toward vinyl isn’t for everyone, so we definitely have CDs available if someone wants to buy those.Collectors Weekly: Third Man Records works with a pretty diverse group of artists. What unifies them?

|

| The Smoke Fairies are an example of a band that has cut a record with Third Man but is not represented by the label in the traditional sense. |

For a band like Dex Romweber Duo, they were coming through Nashville on tour. We thought, “Well, let’s get them in the studio. We’ll record two songs. We’ll take their photo in front of the blue wall and we’ll whip it out as soon as we can.” It’s not like Dex Romweber is calling us and we’re providing tour support.

We’re a label, but not in the way people are used to thinking about. We’re more of an old-style label, just focusing mainly on going from single to single.

The one unifying thing behind pretty much all of our releases is the involvement of Jack White, whether he’s in the band or producing it. In short, it’s his label, and I think his vision is the unifying aspect of all these releases. It is wholly fueled on his energy and what he wants to accomplish.

Collectors Weekly: Are there any other labels out there now with a similar strategy?

Blackwell: There are a lot of labels that do what we do, but they aren’t labels that many people have heard of. The staff here is really into labels like Trouble in Mind or Rob’s House. A label that I really love is In the Red Records. HoZac is another great one. But these all tend to be more independent and underground. For lack of a better term, you could call them hobby labels.Vinyl still has some lead in it. You don’t want to eat it.We’re in a special spot. Because we’re Jack White’s record label, we’re afforded a little bit of a higher profile, and we’re able to sell more records because of it. But we think of ourselves as just a larger version of those so-called hobby labels, labels that put out music they love, focus mainly on singles, and think in terms of working from one project to the next. We’ve been open about a year and a half, and I’ve already assigned 55 catalog numbers. That’s a lot of records to put out.

Collectors Weekly: Why are small labels important?

Blackwell: Smaller record labels will always be important because they are the record labels that discover talent. There are certain obvious exceptions to this rule—John Hammond from Columbia Records discovering Bob Dylan, for example. But Bob Dylan was an undeniable talent. Anyone who saw him would’ve known that. |

| Even though the facilities at Third Man Records in Nashville include a 300-person performance space, the retail space itself is barely 15 by 15 feet. |

Look at Elvis Presley starting with Sun Records before moving on to RCA. Look at Nirvana starting with Sub Pop and moving on to DGC. Look at the White Stripes starting with a single on a small Detroit record label called Italy Records and then moving up to V2 after three albums. All of these are artists that started out on small, independent labels. That seems to be a proven path to success time and time again.

Not to slight any artist that debuted on a major record label, of course. Three of my favorite bands—the Stooges, the Ramones, and the Sex Pistols—were major-label bands that never did anything on small, independent labels to begin with. It’s just that in the world where I grew up and still operate in, independent labels are where the wealth of my music interest and information comes from.

Collectors Weekly: You don’t seem old enough to have come from vinyl roots.

Blackwell: I’m only 28 years old, but I got into Nirvana really early on. One day, I was at a record store called Desirable Discs in Dearborn, Michigan, and I saw a copy of the “Sliver” 7-inch by Nirvana on the wall. |

| Of course, if you are looking for a vinyl copy of the latest White Stripes album, Third Man Records has that, too. |

At the time, I didn’t even have a record player. I was probably 14. I had a job, and I had money, so I found a record player for 15 bucks or so.

From there, I set off buying what I could of Nirvana vinyl. I got the easily obtained stuff, the LPs and the handful of bootlegs, and I expanded from there, thinking, “The Melvins are kind of like Nirvana; I’m going to look for Melvins records.” Then I got into Mudhoney records. Sub Pop’s 1996 mail-order catalog blew it open for me.

Sub Pop did a poster of its first 370 or so releases. I thought it was so cool that I bought the poster and basically used it as my guidebook. That was my no-turning-back point. I started getting records just because they were on Sub Pop; in time I went from, “Wow, I bought this just because it has this logo on it,” to actually liking the bands—the Fastbacks, Eric’s Trip, and bands I hadn’t heard anything about before.

Collectors Weekly: Where did Third Man’s slogan, “Your turntable is not dead,” come from?

Blackwell: Jack originally operated an upholstery business in Detroit called Third Man Upholstery. The motto of Third Man Upholstery printed on Jack’s business card was “Your furniture is not dead.” So Third Man and its slogan were an extension of that, both the motto and the company name, obviously.The overall mindset around here is that just because vinyl records aren’t the medium of choice for the masses doesn’t mean that they’re not viable. Just because no one’s ever going to sell one million copies of an LP ever again—I feel like I can say that as a certain fact—doesn’t mean that vinyl is dead. It’s the format that we believe in.

For example, even though the first music I ever purchased was on vinyl, most of my time growing up was spent listening to music on cassettes and CDs. But vinyl was always in the picture. It’s the format I like most. The 7-inch 45 RPM vinyl single with a picture sleeve is my favorite way to listen to music. It’s quick, easy, and digestible. That’s personally how I like records to be, and how I like listening to music. I like putting down a 7-inch."

(All images courtesy Third Man Records)