We would like to thank the fine publication of Popular Science for being in existence and for growing up reading their sister magazine, Popular Mechanics. Between those two magazines, they have been a well of inspiration unlike any other, well besides Thrasher. We would love to lay claim to a few music and motorcycle mags, but they tend to drift with the tides and none have had as lasting an impact on us as the aforementioned periodicals.

These type of magazines have a solid voice and carry through for generations as they are focused on a plethora of topics but always reign in their subject matter. For example, just found this article over on Popular Science about the History of Recorded Music. If yall have any interest in technology mixed with popular culture, you couldn't pick a better topic to research. As technology morphs and changes certain aspects of life are always at the forefront. Music is continually pushing technology as it is a universal language and one in which the creators and listeners are actively evolving together.

Music to us comes in many forms. Whether it be a the beautiful cacophany of a well tuned v-twin that is hummin' along at 85 mph or a raspy guitar with other worldly screams coming out of an Orange amp, we are fully engulfed in the moment. Read on below about how one great man by the name of Thomas Edison set in a motion a chain of events to which the world has been forever changed.

It Begins With the Invention of the Phonograph: August 1878

When Thomas Edison was only 31 years old, Popular Science profiled him, getting a look inside his shop and talking to him about the best writers of the age. The article cites the carbon telephone and the phonograph as the best of his many inventions, not knowing, of course, that records would one day become ubiquitous before being replaced by CDs, then MP3 players, only to make a comeback among audiophiles.

The phonograph was invented largely by accident, as so many good things are. Edison was tinkering with an automatic transmitter for Morse Code when he realized that the vibration from spoken word could make a needle make an indentation on paper, and an even better one on tinfoil. Then, when the grooves were run under the needle again, his words were spoken back to him and the recording was born.

|

| Thank Thomas Edison for Recorded Music |

Talking Cellulose Thread: December 1922

We can hardly imagine being excited to receive a ball of string in the mail (except, perhaps, for the cats among us), but there was a time when we thought that was the future of correspondence. A device created by a Swiss inventor could record sound patterns on a cellulose thread using a sapphire stylus that could then be listened to using a reproduction machine. When recorded, the thread was small enough to coil up and mail in a standard envelope.

The article says that the machines were implemented in a few business offices, where we imagine the secretaries got rather tangled up.

|

| Human voice is first recorded |

Home Recording of Radio Programs: February 1931

The dawn of the ability to record The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes to listen to over and over again must have been a boon to techies and Arthur Conan Doyle fans alike. In the early 1930s, pre-grooved records eliminated the need for the complicated machine used to guide the needle in recording studios and made it possible to record radio programs, such as Sherlock, and personal messages with the purchase of a recording needle and a microphone.

|

| First Phonograph was created in August 1878 |

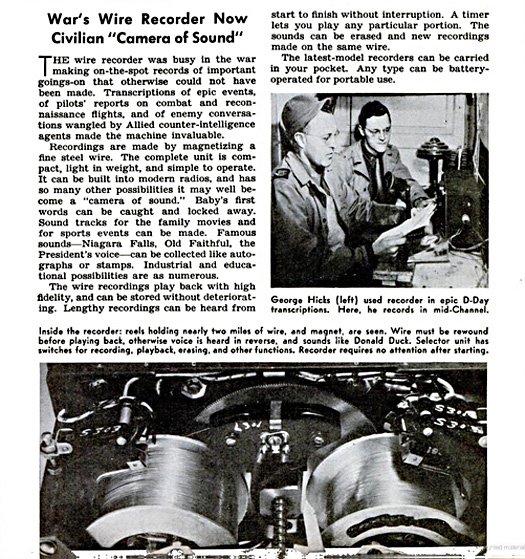

The Camera of Sound: January 1946

During World War II, magnetic wire recorders were used to transmit and store vital information. But once the troops came home, the tool found itself a place among civilians as a way to record family memories, monologues or music off the radio. The recorder is filled with nearly two miles of re-recordable fine steel wire and a magnet. PopSci reminds users to rewind before playing back the recording, or else it plays backwards and "sounds like Donald Duck."

Wireless Record Players: March 1946

For those audiophiles whose crystal clear radios had spoiled them for the "tinny sound" of their old phonographs, PopSci offered a solution. By installing a one-tube oscillator in the record player, it became a miniature broadcasting station that could beam music to radios around the house, as long as they were tuned properly. The article goes on to explain how to walk that fine line between making the broadcast strong enough to be picked up by radios, while not being so strong as to get you in trouble with the FCC.

The Two Types of Continuous Strip Recorders: April 1947

The Two Types of Continuous Strip Recorders: April 1947

The ability to record and play back sound was a boon not just to America in wartime but to parents who wanted to record the cute things their children said, and slow note-taking journalists everywhere. By 1947, you had two options: the recorder that made magnetic impressions on wire or metal-coated paper, or the kind that embossed marks onto film. Putting magnetic material on film made for cheaper recordings, but the film was far less durable than metal wire and harder to edit. PopSci looks at the history of the magnetic recorder, weighs the pros and cons of the different types, and imagines a future where such machines are portable.

Hi-Fi, Explained: March 1957

Hi-Fi, Explained: March 1957

In the early 1950s, being an audiophile made you eccentric, not a hipster. But then high fidelity equipment blew up and became popular for its ability to make the listener feel like they were hearing the music live. While the typical hi-fi set up only truly required a record player, loudspeaker, tuner and amplifier, the obsession with perfecting the sound quality led one man to tweak his system to the tune of 22 additional speakers, after which he still wasn't quite satisfied. The way to tell if the system is perfect? If it can play an ungrooved, unrecorded disk in complete silence without producing any buzzing or humming.

The First In-Car Disc Player: October 1963

The luxury of bringing our music with us wherever we go is something we take for granted these days, often forgetting even the hardships of portable CD players that we wrestled with just over a decade ago. In 1963, PopSci showed readers how to install an in-car record changer that could play up to 14 standard-size, 45 RPM records. Bringing delicate records on car trips along pothole-ridden roads sounds like a recipe for disaster, but according to the article, the device plays without skipping on "moderately bumpy roads" as well as when the car rounds a corner or comes to a stop.

PopSci Tests Your Home Record Player: February 1968

Even the most finicky of ears can have trouble adjusting a hi-fi system to perfection. That's where we stepped in, with our test record full of laboratory-recorded test tones designed to pick up on any flaws in channel balance and sample music pieces that try the limits of a system. And after tweaking their system until it was flawless, lovably pretentious music nerds could use the test record to demonstrate just how awesome their setup was to all their party guests.

Demystifying Tape Systems: Februrary 1969

We got the scoop straight from major tape companies on the pros and cons of five different tape systems: reel-to-reel, cassette, eight-track, four-track and playtape. In 1969, the four-track was already on its way out, with half the playing time and far fewer features than the eight-track. Reel-to-reel systems were also slipping, thanks to the greater convenience of cassette and cartridge systems, and we dismissed playtapes as being for teenagers or children's recordings. That left eight-tracks and cassettes, each with advantages and disadvantages, as top dogs.

The Dawn of the Compact Disc: November 1983

CD players deliver hi-fi without needing the calibrating help of a PopSci test record, completely free of pops or hisses. And the laser beam ensures that the discs never wear out, the way LPs do. We proclaimed the development of CDs to be "the most radical change in record technology since Thomas Edison demonstrated his tinfoil cylinder recordings." At the time of publication, CD players were still too pricey for the average Joe, but costs were already starting to drop (you could get one for less than $600 at Sears).

Sony Mini Disc: August 1991

With records, cassette tapes and CDs all incompatible, Sony decided that what the people needed most was another form of recorded music. With portability in mind, they set about designing the Mini Disc system, which was supposed to have more compressed audio (pros: smaller discs, cons: lower quality), as well as the ability to be jostled without skipping - you could take it on a jog, perhaps. The advantage of choosing to compress the songs rather than develop a new recording technology was that companies would be able to use the same recording equipment they already had to produce the Mini Discs. The discs would also be erasable and re-recordable.

The Gamechanger: January 2002

The first iPod of Apple's dynasty could hold up to 1,000 songs (about 80 CDs worth of music) in its 5 GB of storage. We're used to our teensy iPods now, but the venerable grandpappy wasn't exactly pocket-sized, unless you were wearing cargo pants. It was about 2.5 by 4 inches, weighed 6.5 ounces and had a battery life of around 10 hours.

Full Circle - Ripping Records to an iPod: November 2005

Full Circle - Ripping Records to an iPod: November 2005

Everything old always becomes new again, and recorded music is no exception. When CDs were invented, we praised the superiority of their sound quality to records. But as things became more digitized, vinyl became romanticized, and the natural solution was to rip tracks from records and put them on an iPod. And who better to do the job than a hacker? A DIY-er known only as Mister Jalopy showed PopSci the device he built that automatically transfers songs from a played record to his iPod Mini.